Teddy Bear And Owl Negotiation

Many of us see graduate school as a way to learn and broaden our academic skills as researchers. While this is true, we may forget that the experiences we face in graduate school can also train us for managing life problems in general. Besides continuous stress and drowning in deadlines, one of the key problems graduate students face is negotiating conflict. How do you address disagreements in a diplomatic way that does not “burn the bridge” between you and a fellow student, a faculty member or even your mentor?

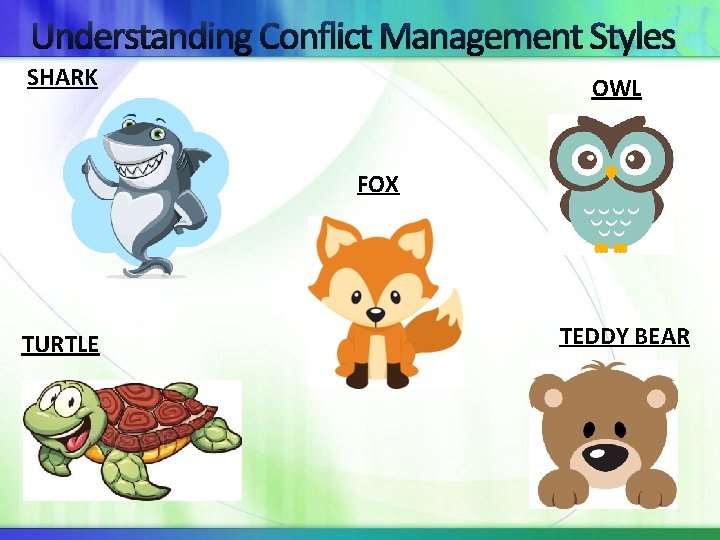

There are a few key identifiers for go-to conflict styles, and different catchy labels are used to help us remember “what we are”. We like to use the Fox, Owl, Shark, Teddy Bear and Turtle. Each is pretty straight-forward, easily associated with common characteristics. Microsoft monthview control 6 0 sp6 excel 2010 download. Cubase 5 mac osx free download. Mar 26, 2018 The personality test is combined of 5 negotiating style that are named after animals: turtle, fox, teddy bear, shark, and owl. The turtle aims at a style which involves avoidance. For younger children, these can be represented as the shark, teddy bear, turtle, fox, and owl. These five behaviors vary on the dimensions of assertiveness and cooperation as well as whether their primary emphasis is outcome or relationship (see Figure 15.1).

This article focuses on an important question for graduate students: How do you negotiate conflict with your mentor? This is important because mentors play a significant role in our lives: they provide guidance as we pursue our research and prepare our theses and dissertations, they approve our moving on to each successive stage of training, and they introduce us to other researchers.

Let’s consider a scenario in which a mentor imposes an additional task on a mentee, even when they are aware of all the responsibilities the mentee already has on their plate. This kind of situation is common and if not handled properly, can lead to some bad arguments and unfortunate experiences in graduate school.

Fortunately, the Conflict Mode Instrument Model (Johnson & Johnson, 1995; Killman & Thomas, 1977) offers five approaches to dealing with such conflict. To make them fun and interesting, each approach is associated with a stylized animal behavior. These approaches are worth considering in deciding how to respond to a conflict between graduate student and advisor.

Here are the five approaches:

Accommodating (teddy bear): Hug me

Teddy Bear And Owl Negotiation Ideas

Like the teddy bear, you can try to be patient. Try your best to accommodate the other person’s need. In this approach, you attempt to maintain the friendly relationship. If you are harboring angry or negative feelings, they are bound to show up eventually — particularly because of how frequently you interact with your mentor. Therefore, sometimes the best way is to let of ill feelings and be accommodating to your mentor’s requests.

Avoiding (the turtle): Hide in your shell

For the time being, avoid the situation and the person entirely so that you avoid a clash. Come back to it later when you have cooled down to explain politely, in writing, or in person why you cannot take up additional work at this time. Or, having thought about it, just take on the additional work for the time being to avoid any conflict. This is helpful in cases when your own tasks can be delayed in order to handle your mentor’s assignment.

Compromising (the fox): Cunning and diplomatic

Simply put, both your tasks and your advisor’s work are important. So, learn to negotiate. First, break down the additional work that has been given to you and prioritize what is more important, specifically for you. For example, would reading those additional three articles and writing a report on them help you to get your name on a poster or paper? Or would running another student’s experiment give you the opportunity to collaborate on that project? Rank what is important and what can be done in a reasonable amount of time, combined with your own work. Then discuss with your advisor so that you can meet halfway. You are not entirely avoiding, rejecting or accommodating their demands but you are meeting some of those demands.

Collaborating (the owl): Wise beyond years

Teddy Bear And Owl Negotiation Game

It may be the best to have a one-on-one talk with your advisor. For example, you can list all the school-related tasks you need to get done that week, show the list to your advisor and ask them to help you prioritize the tasks. That way, the mentor can see things from the mentee’s perspective and help develop solutions. The key goal here is clear communication and collaboration.

Competing (the shark): Eyes for you only

Basically, this means staying committed to your goals, and explaining to the advisor why you cannot fulfill their request. That should be done respectfully and only when your goals are critical (like getting your thesis completed on time). This approach should be taken only after careful thought. It may risk damaging your relationship with the advisor, but it may also serve to enhance the advisor’s respect for you.

There is no one correct style of conflict resolution. Different approaches may be needed for different situations and people. These five options are good starting points for thinking about how to deal with conflicts that many graduate students face.

References

Johnson, D.W., & Johnson, R.T. (1995). Teaching students to be peacemakers: Results of five years of research. Peace and Conflict, 1(4), 417-438.

Kilmann, R.H., & Thomas, K.W. (1977). Developing a forced-choice measure of conflict-handling behavior: The 'MODE' instrument. Educational and psychological measurement, 37(2), 309-325.

About the author

Tasnuva Enam is the cognitive science representative on the APA Science Student Council. She is currently a fourth year graduate student at the University of Alabama. Her research investigates memory, metamemory and aging. Hitman 2 silent assassin download demo.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the opinions or policies of APA.